Using R and Python to Predict Housing Prices

Created:

Some folks work in R. Some work in Python. Some work in both. I’m more on the R side, which has served my needs as a Phd student, but I also use Python on occasion. I thought it would be fun, as an exercise, to do a side-by-side, nose-to-tail analysis in both R and Python, taking advantage of the wonderful {reticulate} package in R. {reticulate} allows one to access Python through the R interface. I find this especially cool in Rmarkdown, since you can knit R and Python chucks in the same document! You can, to some extent, pass objects back and forth between the R and Python environments. Wow.

So given this affordance, I analyze the Ames Housing dataset with the goal of predicting housing prices, a la this Kaggle competition.

I abide by a few rule:

- Be explicit as possible in both languages

- Use a few packages/libraries as possible

- Level playing field–e.g., use the same values for tuning parameters

- Try to replicate the analysis as closely as possible in each language

- Avoid any sort of evaluative comparison

Important note. I primarily use R and have much more experience with R than Python. So bear that in mind.

Let the fun begin.

Importing the libraries

Now, I know I just said that I will use as few libraries as possible–but I will do the R end of this in the {tidyverse} idiom. I will also take a few things from the {tidymodels} suite of packages. I do this because {tidymodels} is the successor to one of the main machine learning packages in R, {caret}.

For Python, I use the usual suspects: {pandas}, {numpy} and {scipy}, and {matplotlib} for visualizations. I also import {seaborn}, again violating my rules, but {seaborn} makes it easy to color visualizations by groups, like in {ggplot2}.

Python

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

from scipy.stats import skew

import seaborn as sns

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

Importing the data

The cool thing about {reticulate} is that it allows you to access objects from either environment. To access a Python object, you use the syntax r.object and in R you use py$object. So in this case, I will import using Python and then call the objects over to the R environment.

This causes an interesting data issue and serves as a good reminder to always check out your data before plunging ahead with analysis. We will see this in the next section.

Python

train = pd.read_csv('train.csv')

test = pd.read_csv('test.csv')

# Keep the IDs from the test data for submission

ids = test['Id']

Using the syntax just described, I will assign the objects in R.

R

train <- py$train

test <- py$test

# Keep IDs for submission

ids <- test %>% pull(Id)

test <- test %>% select(-Id)

# Keep outcome variable

y <- train$SalePrice

Exploratory data analysis

Examining the structure of the data

First, it is always a good idea to know exactly what the data look like. Key questions:

- How many variables/features/columns do I have?

- How many observations/rows do I have?

- What types of variables/features/columns do I have?

- Which variables/features/columns have missing observations and how many?

Let’s do this in R first. Check the dimensions and then the features.

R

print(glue("The training dataset has {ncol(train)} features and {nrow(train)} observations."))

## The training dataset has 81 features and 1460 observations.

R

map_chr(train, class) %>% table() %>% {glue("There are {.} features of type {names(.)}")}

## There are 27 features of type character

## There are 16 features of type list

## There are 38 features of type numeric

I like the glimpse() function from the {tibble} package a lot–it gives the dimension, the features, their type, and a quick glance at each. But it isn’t great where there are a great deal of features. So, check the dimensions first. Here, it’s not bad at all, so I use glimpse() to see the features and their type.

R

glimpse(train)

## Rows: 1,460

## Columns: 81

## $ Id <dbl> 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, …

## $ MSSubClass <dbl> 60, 20, 60, 70, 60, 50, 20, 60, 50, 190, 20, 60, 20, 20…

## $ MSZoning <chr> "RL", "RL", "RL", "RL", "RL", "RL", "RL", "RL", "RM", "…

## $ LotFrontage <dbl> 65, 80, 68, 60, 84, 85, 75, NaN, 51, 50, 70, 85, NaN, 9…

## $ LotArea <dbl> 8450, 9600, 11250, 9550, 14260, 14115, 10084, 10382, 61…

## $ Street <chr> "Pave", "Pave", "Pave", "Pave", "Pave", "Pave", "Pave",…

## $ Alley <list> [NaN, NaN, NaN, NaN, NaN, NaN, NaN, NaN, NaN, NaN, NaN…

## $ LotShape <chr> "Reg", "Reg", "IR1", "IR1", "IR1", "IR1", "Reg", "IR1",…

## $ LandContour <chr> "Lvl", "Lvl", "Lvl", "Lvl", "Lvl", "Lvl", "Lvl", "Lvl",…

## $ Utilities <chr> "AllPub", "AllPub", "AllPub", "AllPub", "AllPub", "AllP…

## $ LotConfig <chr> "Inside", "FR2", "Inside", "Corner", "FR2", "Inside", "…

## $ LandSlope <chr> "Gtl", "Gtl", "Gtl", "Gtl", "Gtl", "Gtl", "Gtl", "Gtl",…

## $ Neighborhood <chr> "CollgCr", "Veenker", "CollgCr", "Crawfor", "NoRidge", …

## $ Condition1 <chr> "Norm", "Feedr", "Norm", "Norm", "Norm", "Norm", "Norm"…

## $ Condition2 <chr> "Norm", "Norm", "Norm", "Norm", "Norm", "Norm", "Norm",…

## $ BldgType <chr> "1Fam", "1Fam", "1Fam", "1Fam", "1Fam", "1Fam", "1Fam",…

## $ HouseStyle <chr> "2Story", "1Story", "2Story", "2Story", "2Story", "1.5F…

## $ OverallQual <dbl> 7, 6, 7, 7, 8, 5, 8, 7, 7, 5, 5, 9, 5, 7, 6, 7, 6, 4, 5…

## $ OverallCond <dbl> 5, 8, 5, 5, 5, 5, 5, 6, 5, 6, 5, 5, 6, 5, 5, 8, 7, 5, 5…

## $ YearBuilt <dbl> 2003, 1976, 2001, 1915, 2000, 1993, 2004, 1973, 1931, 1…

## $ YearRemodAdd <dbl> 2003, 1976, 2002, 1970, 2000, 1995, 2005, 1973, 1950, 1…

## $ RoofStyle <chr> "Gable", "Gable", "Gable", "Gable", "Gable", "Gable", "…

## $ RoofMatl <chr> "CompShg", "CompShg", "CompShg", "CompShg", "CompShg", …

## $ Exterior1st <chr> "VinylSd", "MetalSd", "VinylSd", "Wd Sdng", "VinylSd", …

## $ Exterior2nd <chr> "VinylSd", "MetalSd", "VinylSd", "Wd Shng", "VinylSd", …

## $ MasVnrType <list> ["BrkFace", "None", "BrkFace", "None", "BrkFace", "Non…

## $ MasVnrArea <dbl> 196, 0, 162, 0, 350, 0, 186, 240, 0, 0, 0, 286, 0, 306,…

## $ ExterQual <chr> "Gd", "TA", "Gd", "TA", "Gd", "TA", "Gd", "TA", "TA", "…

## $ ExterCond <chr> "TA", "TA", "TA", "TA", "TA", "TA", "TA", "TA", "TA", "…

## $ Foundation <chr> "PConc", "CBlock", "PConc", "BrkTil", "PConc", "Wood", …

## $ BsmtQual <list> ["Gd", "Gd", "Gd", "TA", "Gd", "Gd", "Ex", "Gd", "TA",…

## $ BsmtCond <list> ["TA", "TA", "TA", "Gd", "TA", "TA", "TA", "TA", "TA",…

## $ BsmtExposure <list> ["No", "Gd", "Mn", "No", "Av", "No", "Av", "Mn", "No",…

## $ BsmtFinType1 <list> ["GLQ", "ALQ", "GLQ", "ALQ", "GLQ", "GLQ", "GLQ", "ALQ…

## $ BsmtFinSF1 <dbl> 706, 978, 486, 216, 655, 732, 1369, 859, 0, 851, 906, 9…

## $ BsmtFinType2 <list> ["Unf", "Unf", "Unf", "Unf", "Unf", "Unf", "Unf", "BLQ…

## $ BsmtFinSF2 <dbl> 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 32, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, …

## $ BsmtUnfSF <dbl> 150, 284, 434, 540, 490, 64, 317, 216, 952, 140, 134, 1…

## $ TotalBsmtSF <dbl> 856, 1262, 920, 756, 1145, 796, 1686, 1107, 952, 991, 1…

## $ Heating <chr> "GasA", "GasA", "GasA", "GasA", "GasA", "GasA", "GasA",…

## $ HeatingQC <chr> "Ex", "Ex", "Ex", "Gd", "Ex", "Ex", "Ex", "Ex", "Gd", "…

## $ CentralAir <chr> "Y", "Y", "Y", "Y", "Y", "Y", "Y", "Y", "Y", "Y", "Y", …

## $ Electrical <list> ["SBrkr", "SBrkr", "SBrkr", "SBrkr", "SBrkr", "SBrkr",…

## $ `1stFlrSF` <dbl> 856, 1262, 920, 961, 1145, 796, 1694, 1107, 1022, 1077,…

## $ `2ndFlrSF` <dbl> 854, 0, 866, 756, 1053, 566, 0, 983, 752, 0, 0, 1142, 0…

## $ LowQualFinSF <dbl> 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0…

## $ GrLivArea <dbl> 1710, 1262, 1786, 1717, 2198, 1362, 1694, 2090, 1774, 1…

## $ BsmtFullBath <dbl> 1, 0, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 0, 1, 1, 1, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1…

## $ BsmtHalfBath <dbl> 0, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0…

## $ FullBath <dbl> 2, 2, 2, 1, 2, 1, 2, 2, 2, 1, 1, 3, 1, 2, 1, 1, 1, 2, 1…

## $ HalfBath <dbl> 1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 1, 0, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0, 0, 1…

## $ BedroomAbvGr <dbl> 3, 3, 3, 3, 4, 1, 3, 3, 2, 2, 3, 4, 2, 3, 2, 2, 2, 2, 3…

## $ KitchenAbvGr <dbl> 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 2, 2, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 2, 1…

## $ KitchenQual <chr> "Gd", "TA", "Gd", "Gd", "Gd", "TA", "Gd", "TA", "TA", "…

## $ TotRmsAbvGrd <dbl> 8, 6, 6, 7, 9, 5, 7, 7, 8, 5, 5, 11, 4, 7, 5, 5, 5, 6, …

## $ Functional <chr> "Typ", "Typ", "Typ", "Typ", "Typ", "Typ", "Typ", "Typ",…

## $ Fireplaces <dbl> 0, 1, 1, 1, 1, 0, 1, 2, 2, 2, 0, 2, 0, 1, 1, 0, 1, 0, 0…

## $ FireplaceQu <list> [NaN, "TA", "TA", "Gd", "TA", NaN, "Gd", "TA", "TA", "…

## $ GarageType <list> ["Attchd", "Attchd", "Attchd", "Detchd", "Attchd", "At…

## $ GarageYrBlt <dbl> 2003, 1976, 2001, 1998, 2000, 1993, 2004, 1973, 1931, 1…

## $ GarageFinish <list> ["RFn", "RFn", "RFn", "Unf", "RFn", "Unf", "RFn", "RFn…

## $ GarageCars <dbl> 2, 2, 2, 3, 3, 2, 2, 2, 2, 1, 1, 3, 1, 3, 1, 2, 2, 2, 2…

## $ GarageArea <dbl> 548, 460, 608, 642, 836, 480, 636, 484, 468, 205, 384, …

## $ GarageQual <list> ["TA", "TA", "TA", "TA", "TA", "TA", "TA", "TA", "Fa",…

## $ GarageCond <list> ["TA", "TA", "TA", "TA", "TA", "TA", "TA", "TA", "TA",…

## $ PavedDrive <chr> "Y", "Y", "Y", "Y", "Y", "Y", "Y", "Y", "Y", "Y", "Y", …

## $ WoodDeckSF <dbl> 0, 298, 0, 0, 192, 40, 255, 235, 90, 0, 0, 147, 140, 16…

## $ OpenPorchSF <dbl> 61, 0, 42, 35, 84, 30, 57, 204, 0, 4, 0, 21, 0, 33, 213…

## $ EnclosedPorch <dbl> 0, 0, 0, 272, 0, 0, 0, 228, 205, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 176, 0,…

## $ `3SsnPorch` <dbl> 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 320, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0,…

## $ ScreenPorch <dbl> 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 176, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0,…

## $ PoolArea <dbl> 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0…

## $ PoolQC <list> [NaN, NaN, NaN, NaN, NaN, NaN, NaN, NaN, NaN, NaN, NaN…

## $ Fence <list> [NaN, NaN, NaN, NaN, NaN, "MnPrv", NaN, NaN, NaN, NaN,…

## $ MiscFeature <list> [NaN, NaN, NaN, NaN, NaN, "Shed", NaN, "Shed", NaN, Na…

## $ MiscVal <dbl> 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 700, 0, 350, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 700…

## $ MoSold <dbl> 2, 5, 9, 2, 12, 10, 8, 11, 4, 1, 2, 7, 9, 8, 5, 7, 3, 1…

## $ YrSold <dbl> 2008, 2007, 2008, 2006, 2008, 2009, 2007, 2009, 2008, 2…

## $ SaleType <chr> "WD", "WD", "WD", "WD", "WD", "WD", "WD", "WD", "WD", "…

## $ SaleCondition <chr> "Normal", "Normal", "Normal", "Abnorml", "Normal", "Nor…

## $ SalePrice <dbl> 208500, 181500, 223500, 140000, 250000, 143000, 307000,…

Before moving onto Python, notice that some of the features are of class list. This is an artifact of importing via Python and then calling into the R environment. So we have some cleaning up to do. No problem. First, we will unlist() those features and then make sure that the missing values are encoded correctly, since, as you will see, the missing values are encoded now as strings!

R

train <- train %>% mutate_if(is.list, unlist)

train <- train %>% na_if("NaN")

test <- test %>% mutate_if(is.list, unlist)

test <- test %>% na_if("NaN")

any(map_lgl(train, is.list))

## [1] FALSE

That looks much better.

Now, I will do the same thing in Python. Quick reminder that Python is zero-indexed!!

Python

print("The training dataset has %s features and %s observations" % (train.shape[1], train.shape[0]))

#for col in train.columns:

# print("Feature {} is of type {}".format(col, train[[col]].dtypes[0]))

## The training dataset has 81 features and 1460 observations

Python

for name, val in zip(list(train.dtypes.value_counts().index), train.dtypes.value_counts()):

print('There are {} features of type {}'.format(val, name))

## There are 43 features of type object

## There are 35 features of type int64

## There are 3 features of type float64

The method head() in {pandas} does something similar to glimpse(). It gives the number of features along with the first n observation (by default 5, but I will use 10). Unlike glimpse() it does not give the type of each feature. But that’s okay, we just got that information.

Python

train.head(10)

## Id MSSubClass MSZoning ... SaleType SaleCondition SalePrice

## 0 1 60 RL ... WD Normal 208500

## 1 2 20 RL ... WD Normal 181500

## 2 3 60 RL ... WD Normal 223500

## 3 4 70 RL ... WD Abnorml 140000

## 4 5 60 RL ... WD Normal 250000

## 5 6 50 RL ... WD Normal 143000

## 6 7 20 RL ... WD Normal 307000

## 7 8 60 RL ... WD Normal 200000

## 8 9 50 RM ... WD Abnorml 129900

## 9 10 190 RL ... WD Normal 118000

##

## [10 rows x 81 columns]

So we know there are 81 features and 1,460 observations. Very important for getting aquainted with a new dataset is to understand the missing data–which features have missing observations and how many. Just as important is to know (or figure out) the process by which missing values are generated. Is it due to random or systematic? Is it due to non-compliance/non-reporting? Data entry mistakes? Missing due to specific suppression rules? In the case of this data, the missing values are meaningful. Missing often–but not always–means “This house does not have this feature.” Right now, we will just describe the missing data.

First, in R. There are many ways to approach this. A simple way is train %>% summarise_all(~sum(is.na(.))), but the output is not reader-friendly. So I’ll pretty it up a bit. Note: wrapping the map2 function in {} prevents the piped data frame from being used as the first argument–we need that in order to call .[["name"]] and .[["value"]] as the two variables to loop over.

R

map_dbl(train, ~ sum(is.na(.x))) %>%

table() %>%

{glue("There {ifelse(. == 1, 'is', 'are')} {.} {ifelse(. == 1, 'feature', 'features')} with {names(.)} missing values")}

## There are 62 features with 0 missing values

## There is 1 feature with 1 missing values

## There are 2 features with 8 missing values

## There are 3 features with 37 missing values

## There are 2 features with 38 missing values

## There are 5 features with 81 missing values

## There is 1 feature with 259 missing values

## There is 1 feature with 690 missing values

## There is 1 feature with 1179 missing values

## There is 1 feature with 1369 missing values

## There is 1 feature with 1406 missing values

## There is 1 feature with 1453 missing values

Okay. Now we know that there is some missing data that we need to deal with. Most of the features are complete, some are missing a handful of observations, and a few are missing A LOT.

Let’s take a closer look at the features with missing data. Which ones are they?

R

train %>%

summarise_all(~sum(is.na(.))) %>%

pivot_longer(cols = everything()) %>%

filter(value != 0) %>%

arrange(desc(value)) %>%

{glue("{.[['name']]} has {.[['value']]} missing observations")}

## PoolQC has 1453 missing observations

## MiscFeature has 1406 missing observations

## Alley has 1369 missing observations

## Fence has 1179 missing observations

## FireplaceQu has 690 missing observations

## LotFrontage has 259 missing observations

## GarageType has 81 missing observations

## GarageYrBlt has 81 missing observations

## GarageFinish has 81 missing observations

## GarageQual has 81 missing observations

## GarageCond has 81 missing observations

## BsmtExposure has 38 missing observations

## BsmtFinType2 has 38 missing observations

## BsmtQual has 37 missing observations

## BsmtCond has 37 missing observations

## BsmtFinType1 has 37 missing observations

## MasVnrType has 8 missing observations

## MasVnrArea has 8 missing observations

## Electrical has 1 missing observations

We can also do this by percent, which provides an additional layer of information.

R

train %>%

summarise_all(~round(sum(is.na(.))/length(.), 4) * 100) %>%

pivot_longer(cols = everything()) %>%

filter(value != 0) %>%

arrange(desc(value)) %>%

{glue("{.[['name']]} has {.[['value']]}% missing observations")}

## PoolQC has 99.52% missing observations

## MiscFeature has 96.3% missing observations

## Alley has 93.77% missing observations

## Fence has 80.75% missing observations

## FireplaceQu has 47.26% missing observations

## LotFrontage has 17.74% missing observations

## GarageType has 5.55% missing observations

## GarageYrBlt has 5.55% missing observations

## GarageFinish has 5.55% missing observations

## GarageQual has 5.55% missing observations

## GarageCond has 5.55% missing observations

## BsmtExposure has 2.6% missing observations

## BsmtFinType2 has 2.6% missing observations

## BsmtQual has 2.53% missing observations

## BsmtCond has 2.53% missing observations

## BsmtFinType1 has 2.53% missing observations

## MasVnrType has 0.55% missing observations

## MasVnrArea has 0.55% missing observations

## Electrical has 0.07% missing observations

Now to do this in Python. {pandas} has a nifty is.null() method that we an chain with sum() to get the number of missing values in a series.

Python

mv = train.isnull().sum()

mv = mv[mv!=0].sort_values(ascending=False)

for name, val in zip(list(mv.index), mv):

print("{} has {} missing values".format(name, val))

## PoolQC has 1453 missing values

## MiscFeature has 1406 missing values

## Alley has 1369 missing values

## Fence has 1179 missing values

## FireplaceQu has 690 missing values

## LotFrontage has 259 missing values

## GarageYrBlt has 81 missing values

## GarageType has 81 missing values

## GarageFinish has 81 missing values

## GarageQual has 81 missing values

## GarageCond has 81 missing values

## BsmtFinType2 has 38 missing values

## BsmtExposure has 38 missing values

## BsmtFinType1 has 37 missing values

## BsmtCond has 37 missing values

## BsmtQual has 37 missing values

## MasVnrArea has 8 missing values

## MasVnrType has 8 missing values

## Electrical has 1 missing values

And dividing by the length of the series gets us the proportion.

Python

mv = (train.isnull().sum()/len(train))*100

mv = mv[mv!=0].sort_values(ascending=False).round(2)

for name, val in zip(list(mv.index), mv):

print("{} has {}% missing values".format(name, val))

## PoolQC has 99.52% missing values

## MiscFeature has 96.3% missing values

## Alley has 93.77% missing values

## Fence has 80.75% missing values

## FireplaceQu has 47.26% missing values

## LotFrontage has 17.74% missing values

## GarageYrBlt has 5.55% missing values

## GarageType has 5.55% missing values

## GarageFinish has 5.55% missing values

## GarageQual has 5.55% missing values

## GarageCond has 5.55% missing values

## BsmtFinType2 has 2.6% missing values

## BsmtExposure has 2.6% missing values

## BsmtFinType1 has 2.53% missing values

## BsmtCond has 2.53% missing values

## BsmtQual has 2.53% missing values

## MasVnrArea has 0.55% missing values

## MasVnrType has 0.55% missing values

## Electrical has 0.07% missing values

Exploring the target feature/dependent variable/outcome

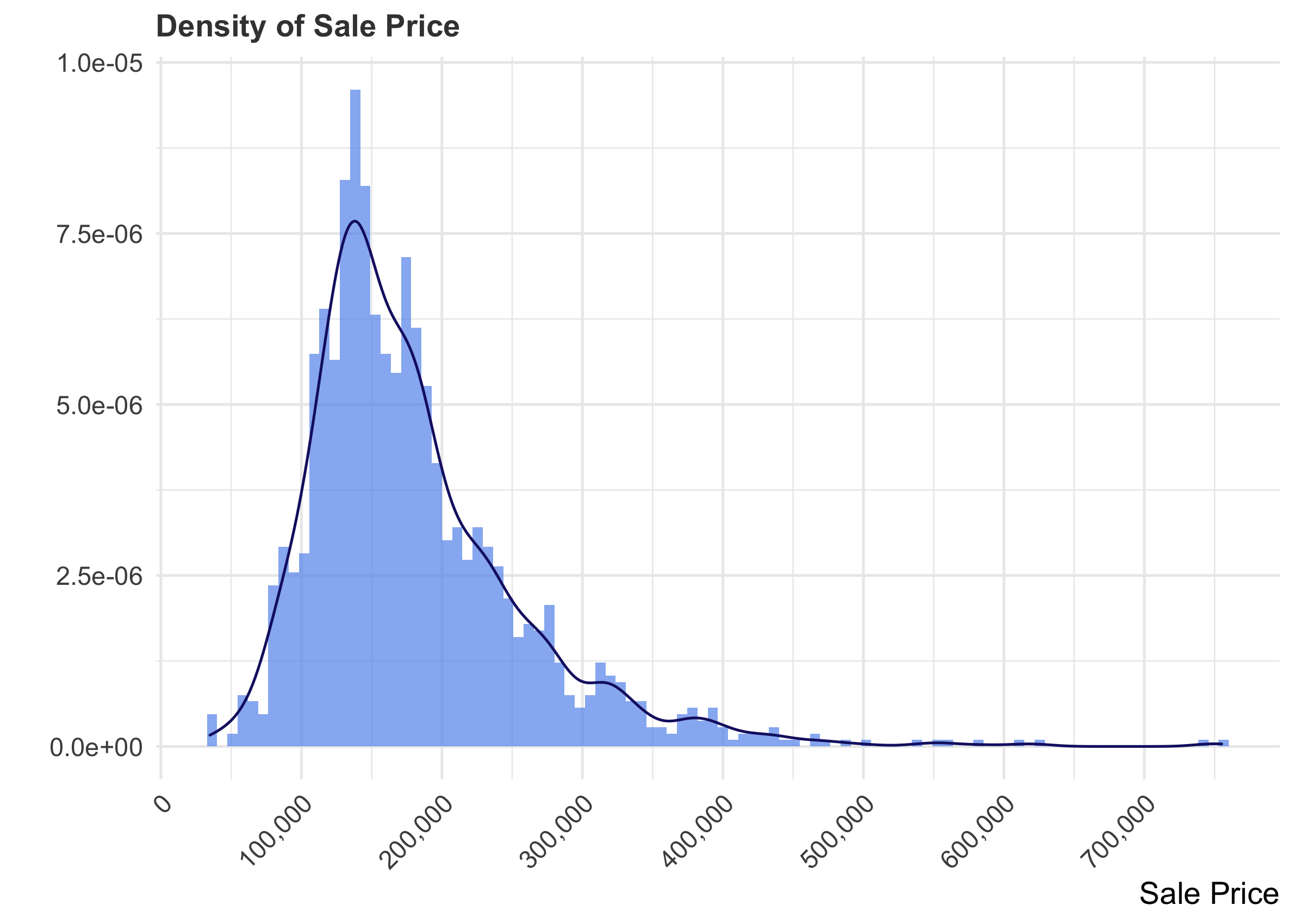

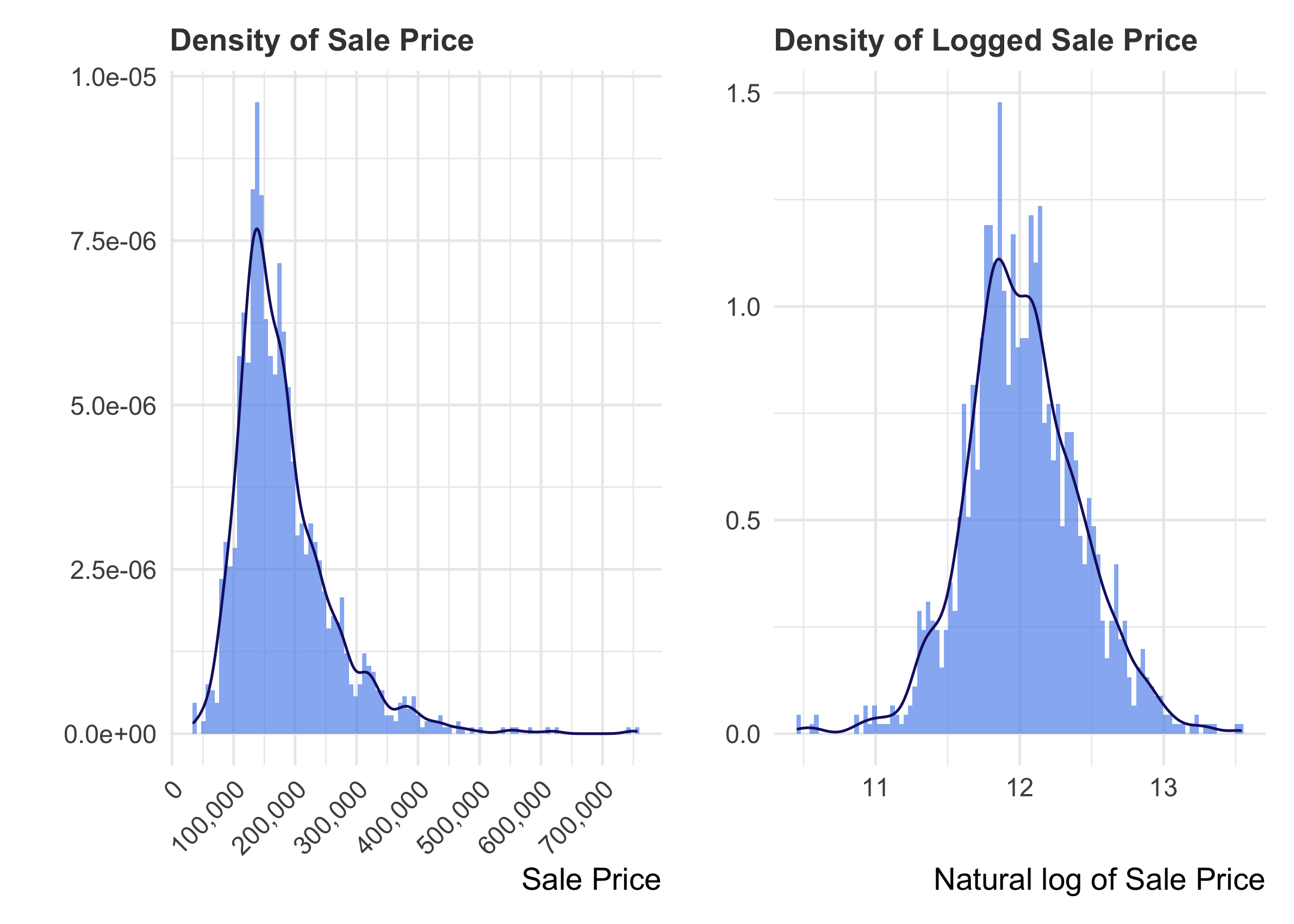

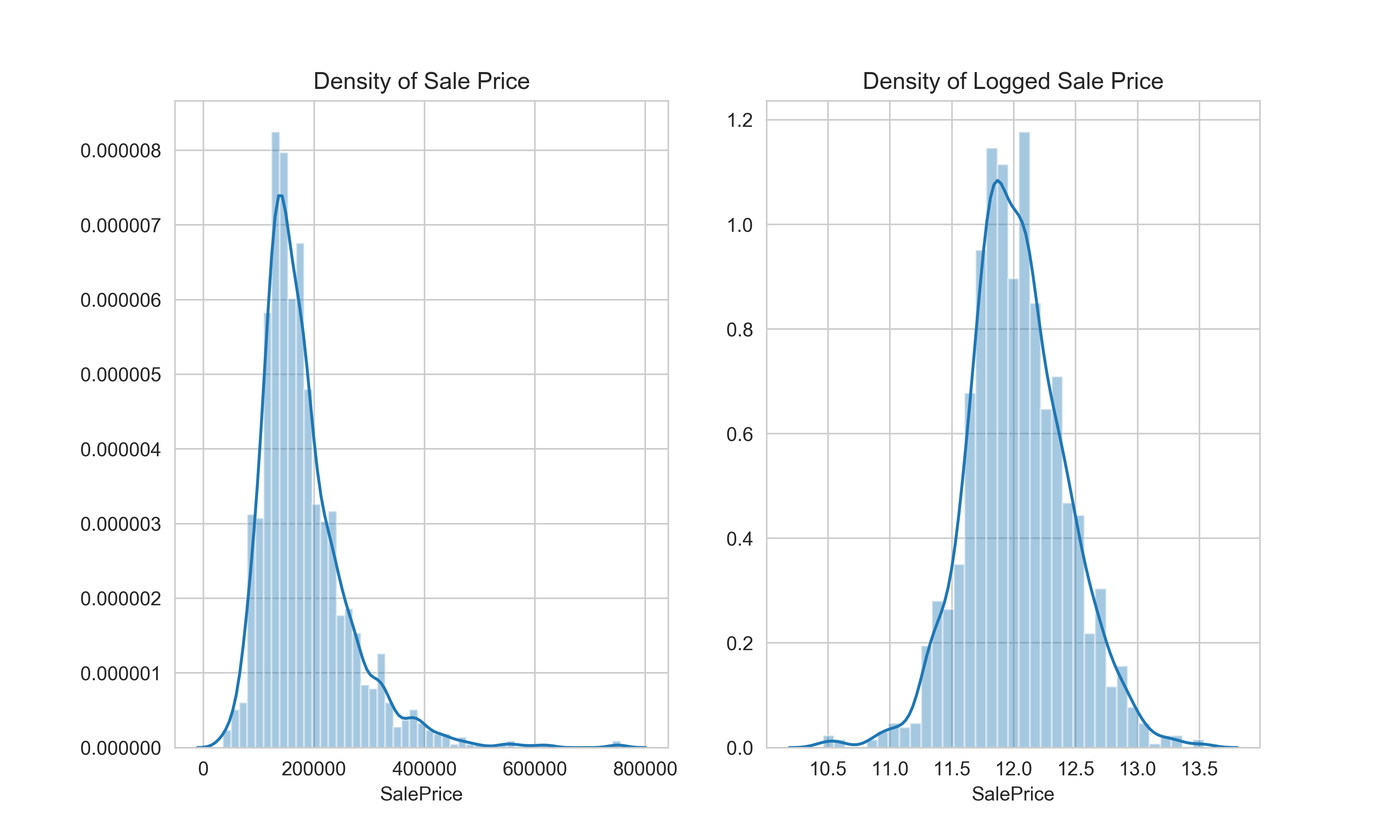

Attending to the characteristics of the target variable is a critical part of data exploration. It helps to visualize the distribution to determine the type of analysis you might want to carry out.

Knowing to content domain, we would not be surprised to see that the distribution is right-skewed, as things like housing prices, income, etc. often are.

R

p1 <- train %>%

ggplot(aes(x = SalePrice)) +

geom_histogram(aes(x = SalePrice, stat(density)),

bins = 100,

fill = "cornflowerblue",

alpha = 0.7) +

geom_density(color = "midnightblue") +

scale_x_continuous(breaks= seq(0, 800000, by=100000), labels = scales::comma) +

labs(x = "Sale Price", y = "", title = "Density of Sale Price") +

theme(axis.text.x = element_text(size = 10, angle = 45, hjust = 1))

p1

In such cases, it is useful to take the log of the feature in order to normalize its distribution. That way, it satisfies the expectations of linear modeling.

R

p2 <- train %>%

ggplot() +

geom_histogram(aes(x = log(SalePrice), stat(density)),

bins = 100,

fill = "cornflowerblue",

alpha = 0.7) +

geom_density(aes(x = log(SalePrice)), color = "midnightblue") +

labs(x = "Natural log of Sale Price", y = "", title = "Density of Logged Sale Price")

p1 + p2

Again, in Python, looking at the plots side by side.

Python

y = train['SalePrice']

sns.set_style("whitegrid")

fig, ax = plt.subplots(1, 2, sharey=False, sharex=False, figsize=(10,6))

sns.distplot(y, ax=ax[0]).set(title='Density of Sale Price')

sns.distplot(np.log(y), ax=ax[1]).set(title='Density of Logged Sale Price')

That looks much better. Next, let’s explore the features.

Exploring some bivariate relationships

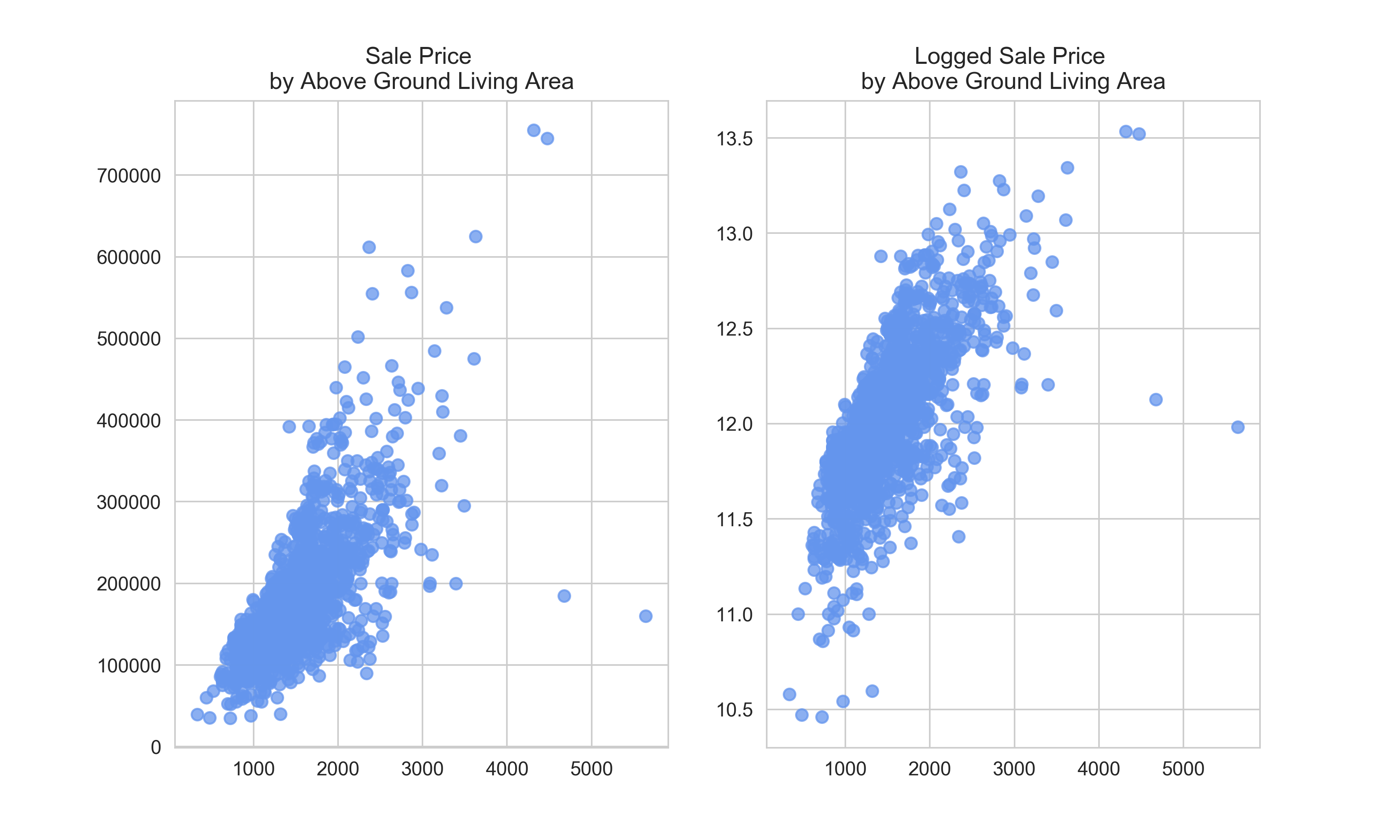

We might guess, based on our prior knowledge, that there is a meaningful positive relationship between how much a house costs and how big it is.

R

p1 <- train %>%

ggplot(aes(x = GrLivArea, y = SalePrice)) +

geom_point(color = "cornflowerblue", alpha = 0.75) +

scale_y_continuous(breaks= seq(0, 800000, by=200000), labels = scales::comma) +

labs(x = "Above ground living area", y = "Sale Price", title = "Sale Price \nby Above Ground Living Area")

p2 <- train %>%

ggplot(aes(x = GrLivArea, y = log10(SalePrice))) +

geom_point(color = "cornflowerblue", alpha = 0.75) +

labs(x = "Above ground living area", y = "Log of Sale Price", title = "Logged Sale Price \nby Above Ground Living Area")

p1 + p2

In Python, we can use {matplotlib} to see this relationship.

Python

fig, ax = plt.subplots(1, 2, sharey=False, sharex=False, figsize=(10,6))

ax[0].scatter(train['GrLivArea'], train['SalePrice'], alpha = 0.75, color = '#6495ED')

ax[0].set_title('Sale Price \nby Above Ground Living Area')

ax[1].scatter(train['GrLivArea'], np.log(train['SalePrice']), alpha = 0.75, color = '#6495ED')

ax[1].set_title('Logged Sale Price \nby Above Ground Living Area')

plt.show()

In both plots, we can see a few outliers–partularly the houses with relative low sale prices given their above ground living area. It would be wise to drop these, since there are probably reasons that they are unusual and our features won’t pick that up.

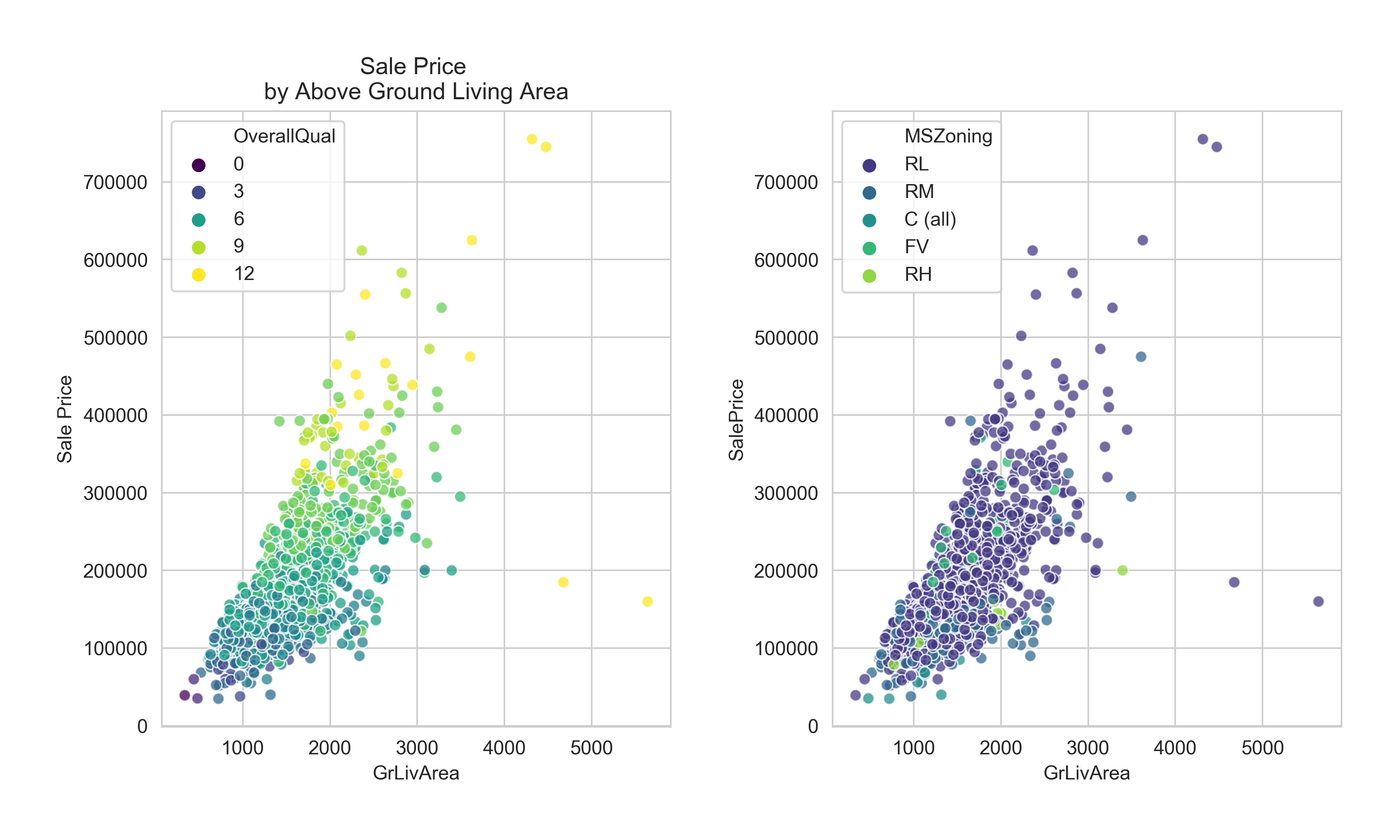

But, out of curiosity, let’s see if there is some reason in the data why these house sold for so little money. Perhaps it has to do with the overall quality of the house? Its type? Its zoning? Its location?

R

p1 <- train %>%

ggplot(aes(x = GrLivArea, y = SalePrice)) +

geom_point(aes(color = factor(OverallQual)), alpha = 0.75) +

scale_color_viridis_d(name = "Overall Quality",

breaks = c("2", "4", "6", "8", "10")) +

scale_y_continuous(breaks= seq(0, 800000, by=200000), labels = scales::comma) +

labs(x = "Above ground living area", y = "Sale Price", title = "Sale Price \nby Above Ground Living Area") +

theme(legend.position = c(0.2, 0.8),

legend.title = element_text(size = 8),

legend.text = element_text(size = 6),

legend.background = element_blank(),

legend.key.size = unit(5, "mm"),

#legend.box.background = element_rect(color = "black", fill = "transparent"),

legend.margin = ggplot2::margin(0.1, 0.1, 0.1, 0.1, "cm"))

p2 <-

train %>%

mutate(MSZoning = factor(MSZoning, levels = c("RL", "RM", "C (all)", "FV", "RH"))) %>%

ggplot(aes(x = GrLivArea, y = SalePrice)) +

geom_point(aes(color = MSZoning), alpha = 0.75) +

scale_color_viridis_d(name = "Zoning", end = 0.7) +

scale_y_continuous(breaks= seq(0, 800000, by=200000), labels = scales::comma) +

labs(x = "Above ground living area", y = "Sale Price", title = "Sale Price \nby Above Ground Living Area") +

theme(legend.position = c(0.2, 0.8),

legend.title = element_text(size = 8),

legend.text = element_text(size = 6),

legend.background = element_blank(),

legend.key.size = unit(5, "mm"),

#legend.box.background = element_rect(color = "black", fill = "transparent"),

legend.margin = ggplot2::margin(0.1, 0.1, 0.1, 0.1, "cm"))

p1 + p2

For my Python version, I will use {seaborn} rather than straight {matplotlib} to easily color the points by category.

Python

fig, ax = plt.subplots(1, 2, sharey=False, sharex=False, figsize=(10,6))

sns.scatterplot('GrLivArea', 'SalePrice', hue='OverallQual', data=train, palette='viridis', ax=ax[0], alpha=0.75)

ax[0].set_title('Sale Price \nby Above Ground Living Area')

ax[0].set_ylabel('Sale Price')

sns.scatterplot('GrLivArea', 'SalePrice', hue='MSZoning', data=train, palette='viridis', ax=ax[1], alpha=0.75)

#ax[1].set(title='Sale Price \nby Above Ground Living Area', xlabel='Above ground living area', ylabel = 'Sale Price')

fig.tight_layout(pad=3.0)

plt.show()

We should drop those outliers.

R

train <-

train %>%

filter(

!(GrLivArea > 4000 & SalePrice < 200000)

)

In Python too!

Python

train.drop(train[(train['GrLivArea']>4000) & (train['SalePrice']<300000)].index, inplace = True)

Dealing with missing values

We saw before that there are many features without missing values, but a bunch that have a lot. For some of those features, the missing values are meaningful–missing indicates that the house lacks that feature. Take, for example, pools. The feature PoolQC, indicate pool quality, has 1452 missing observations. They are missing because a pool that doesn’t exist can’t be assigned a quality! For features like this, it might make sense to assign a value like None if it is categorical and 0 if it is numeric. There are sets of related features–for example, those related to basements. If a home does not have a basement, clearly it will not have quality, condition, square footage, etc. related to that basement. So, for the categorical values, I will replace missing with None and for the numeric, I will replace missing with 0.

There are a handful of other features were is seems like we have true missing values–missing for some unknown reason, but certainly present in reality. For example, the KitchenQual feature. Certainly, all the homes in this dataset have kitchens, as I believe that is a legal requirement! So, this value is likely missing at random. There are a variety of imputation strategies. I will impute by the mode of the neighborhood and subclass, on the reasoning that homes within neighborhoods and classes are often similar. We might also consider a more sophisticated approach using regression or classification approaches.

To do this, we want to combine the training and testing data so we can fixing the missing values and do the feature engineering all at once. And any scaling or centering we do, we want to do on the all the data at our disposal. We should also drop the target and the ID feature.

R

all_dat <- bind_rows(train, test) %>%

select(-Id, -SalePrice)

none_vars <- c("BsmtCond",

"BsmtQual",

"BsmtExposure",

"BsmtFinType1",

"BsmtFinType2",

"MasVnrType",

"GarageType",

"GarageFinish",

"GarageQual",

"GarageCond",

"Alley",

"Fence",

"FireplaceQu",

"MiscFeature",

"PoolQC")

all_dat <-

all_dat %>%

mutate_at(vars(all_of(none_vars)), ~ replace_na(., "None"))

zero_vars <- c("MasVnrArea",

"BsmtFinSF1",

"BsmtFinSF2",

"BsmtFullBath",

"BsmtHalfBath",

"BsmtUnfSF",

"TotalBsmtSF",

"GarageArea",

"GarageCars",

"GarageYrBlt")

all_dat <-

all_dat %>%

mutate_at(vars(all_of(zero_vars)), ~ replace_na(., 0))

In Python, I will do the same thing using for loops for the relevant features, taking advantage of {pandas} fillna() method.

Python

all_dat = pd.concat((train, test), sort = False, ignore_index = True)

all_dat.drop(['Id', 'SalePrice'], axis = 1, inplace = True)

# None vars

none_vars = ['BsmtCond',

'BsmtQual',

'BsmtExposure',

'BsmtFinType1',

'BsmtFinType2',

'MasVnrType',

'GarageType',

'GarageFinish',

'GarageQual',

'GarageCond',

'Alley',

'Fence',

'FireplaceQu',

'MiscFeature',

'PoolQC']

for var in none_vars:

all_dat[var] = all_dat[var].fillna('None')

# Zero vars

zero_vars = ['MasVnrArea',

'BsmtFinSF1',

'BsmtFinSF2',

'BsmtFullBath',

'BsmtHalfBath',

'BsmtUnfSF',

'TotalBsmtSF',

'GarageArea',

'GarageCars',

'GarageYrBlt']

for var in zero_vars:

all_dat[var] = all_dat[var].fillna(0)

Moving on to the observations missing at random. Most of these are categorical, and so I impute the mode. For the numeric feature–LotFrontage–I impute the median. Don’t forget to ungroup()!

R

random_vars <- c("Electrical", "Exterior1st", "Exterior2nd", "Functional", "KitchenQual", "MSZoning", "SaleType", "Utilities")

all_dat <-

all_dat %>%

group_by(Neighborhood, MSSubClass) %>%

mutate_at(vars(all_of(random_vars)), ~ ifelse(is.na(.), which.max(table(.)) %>% names(), .)) %>%

group_by(Neighborhood) %>%

mutate(LotFrontage = ifelse(is.na(LotFrontage), median(LotFrontage, na.rm = TRUE), LotFrontage)) %>%

ungroup()

In Python, the approach is similar, using the groupby() method to group by neighborhood and class, along with the fillna() method. This approach uses a lambda function within a for loop. This is like using an anonymous function within an apply loop in R.

Python

random_vars = ['Electrical', 'Exterior1st', 'Exterior2nd', 'Functional', 'KitchenQual', 'MSZoning', 'SaleType', 'Utilities']

for var in random_vars:

all_dat[var] = all_dat.groupby(['Neighborhood', 'MSSubClass'])[var].apply(lambda x: x.fillna(x.mode()[0]))

all_dat['LotFrontage'] = all_dat.groupby(['Neighborhood'])['LotFrontage'].apply(lambda x: x.fillna(x.median()))

Now, we should have NO missing values in our data!

R

glue("There are {sum(is.na(all_dat))} features with missing observations")

## There are 0 features with missing observations

Python

missing = all_dat.apply(lambda x: x.isnull().sum()) > 0

print('There are {} features with missing observations'.format(missing.sum()))

## There are 0 features with missing observations

Feature engineering

To try to extract all the predictive power possible in the data available at our disposal, we should create some new features. Creating new features is based on domain knowledge, data exploration, trial-and-error, and intuition. I don’t think there is anything special here. Presumably, there is a strong association between the square footage of a house and its ultimate selling price. Too eek out a bit more predictive power, I create features for the total area, the average room size, the total number of baths, the total outside area, and quadratic terms for the total square footage and overall quality.

In R, I create these feeatures using mutate() from {dplyr} in a single pipe.

R

all_dat <-

all_dat %>%

mutate(TotalArea = `1stFlrSF` + `2ndFlrSF` + TotalBsmtSF,

AvgRmSF = GrLivArea / TotRmsAbvGrd,

TotalBaths = FullBath + (HalfBath * 0.5) + BsmtFullBath + (BsmtHalfBath * 0.5),

OutsideArea = OpenPorchSF + `3SsnPorch` + EnclosedPorch + ScreenPorch + WoodDeckSF

) %>%

mutate(TotalArea2 = TotalArea^2,

OverallQual2 = OverallQual^2)

In Python, I create them one at a time.

Python

# Feature engineering

all_dat['TotalArea'] = all_dat['1stFlrSF'] + all_dat['2ndFlrSF'] + all_dat['TotalBsmtSF']

all_dat['AvgRmSF'] = all_dat['GrLivArea'] / all_dat['TotRmsAbvGrd']

all_dat['TotalBaths'] = all_dat['FullBath'] + (all_dat['HalfBath'] * 0.5) + all_dat['BsmtFullBath'] + (all_dat['BsmtHalfBath'] * 0.5)

all_dat['OutsideArea'] = all_dat['OpenPorchSF'] + all_dat['3SsnPorch'] + all_dat['EnclosedPorch'] + all_dat['ScreenPorch'] + all_dat['WoodDeckSF']

all_dat['TotalArea2'] = all_dat['TotalArea']**2

all_dat['OverallQual2'] = all_dat['OverallQual']**2

Now that I have created the new features, I want to manipulate the existing ones to prepare for the analysis.

Some of the features are ordinal–the values have inherent ordered meaning in the levels. These are these quality and condition features. I also take some of the “finish” features as ordinal. This is a bit less clear, but there does seem some inherent ordering to the differeny types of finishes.I will convert these to factors in R and label the levels.

R

qual_vars = c("BsmtCond", "BsmtQual", "ExterCond",

"ExterQual", "FireplaceQu", "GarageCond",

"GarageQual", "HeatingQC", "KitchenQual", "PoolQC")

all_dat <-

all_dat %>%

mutate_at(vars(all_of(qual_vars)), ~ factor(.,

levels = c("None",

"Po",

"Fa",

"TA",

"Gd",

"Ex"),

ordered = TRUE)) %>%

mutate(Functional = factor(Functional,

levels = c("Sev",

"Maj1",

"Maj2",

"Mod",

"Min1",

"Min2",

"Typ"),

ordered = TRUE),

GarageFinish = factor(GarageFinish,

levels = c("None",

"Unf",

"RFn",

"Fin"),

ordered = TRUE),

BsmtFinType1 = factor(BsmtFinType1,

levels = c("None",

"Unf",

"LwQ",

"Rec",

"BLQ",

"ALQ",

"GLQ"),

ordered = TRUE),

BsmtFinType2 = factor(BsmtFinType2,

levels = c("None",

"Unf",

"LwQ",

"Rec",

"BLQ",

"ALQ",

"GLQ"),

ordered = TRUE))

# To make these match the features in Python, I'm going to convert them to numeric

all_dat <-

all_dat %>%

mutate_at(vars(all_of(qual_vars),

contains("BsmtFin"),

Functional,

GarageFinish),

~ as.numeric(.))

The processes is similar in Python, but takes advantage of the dictionary type, which does not exist in R. I define as dictionaries relating the labels to numeric values and recode the features using the dictionaries.

Python

qual = {'None': 1, 'Po': 2, 'Fa': 3, 'TA': 4, 'Gd': 5, 'Ex': 6}

func = {'Sev': 1, 'Maj1': 2, 'Maj2': 3, 'Mod': 4, 'Min1': 5, 'Min2': 6, 'Typ': 7}

fin = {'None': 1, 'Unf': 2, 'RFn': 3, 'Fin': 4}

bsmt_fin = {'None': 1, 'Unf': 2, 'LwQ': 3, 'Rec': 4, 'BLQ': 5, 'ALQ': 6, 'GLQ': 7}

qual_vars = ['BsmtCond', 'BsmtQual', 'ExterCond',

'ExterQual', 'FireplaceQu', 'GarageCond',

'GarageQual', 'HeatingQC', 'KitchenQual', 'PoolQC']

for var in qual_vars:

all_dat[var] = all_dat[var].map(qual)

all_dat['Functional'] = all_dat['Functional'].map(func)

all_dat['GarageFinish'] = all_dat['GarageFinish'].map(fin)

all_dat['BsmtFinType1'] = all_dat['BsmtFinType1'].map(bsmt_fin)

all_dat['BsmtFinType2'] = all_dat['BsmtFinType2'].map(bsmt_fin)

There are some numeric features that are really categorical, so we should encode these as well. However, they are not ordinal and so we can convert them to strings. These include year, month, and subclass.

R

nominal_vars = c("Alley", "BldgType", "Condition1", "Condition2", "Electrical",

"Exterior1st", "Exterior2nd", "Fence", "Foundation", "GarageType",

"Heating", "HouseStyle", "LandContour", "LotConfig", "MSSubClass",

"MSZoning", "MasVnrType", "MiscFeature", "MoSold", "Neighborhood",

"RoofMatl", "RoofStyle", "SaleCondition", "SaleType", "YrSold",

"CentralAir", "BsmtExposure", "LandSlope", "LotShape", "PavedDrive",

"YearBuilt", "YearRemodAdd", "Street", "Utilities")

all_dat <-

all_dat %>%

mutate_at(vars(all_of(nominal_vars)), as.character)

This looks very similar in Python.

Python

nominal_vars = ['Alley', 'BldgType', 'Condition1', 'Condition2', 'Electrical',

'Exterior1st', 'Exterior2nd', 'Fence', 'Foundation', 'GarageType',

'Heating', 'HouseStyle', 'LandContour', 'LotConfig', 'MSSubClass',

'MSZoning', 'MasVnrType', 'MiscFeature', 'MoSold', 'Neighborhood',

'RoofMatl', 'RoofStyle', 'SaleCondition', 'SaleType', 'YrSold',

'CentralAir', 'BsmtExposure', 'LandSlope', 'LotShape', 'PavedDrive',

'YearBuilt', 'YearRemodAdd', 'Street', 'Utilities']

for var in nominal_vars:

all_dat[var] = all_dat[var].astype(str)

I will use one-hot encoding to turn nominal features into dummies. In Python, {pandas} has a built-in method to accomplish this. In R, one can use getDummies() from the {caret} package–which is superseded a bit by the step_dummy() function in {recipes}. But I’ll use the base R approach to avoid adding any additional packages into the mix.

R

dummies <- model.matrix(~., data = all_dat %>% select_if(is.character)) %>% as_tibble() %>% select(-contains("Inter"))

all_dat <-

all_dat %>%

select_if(negate(is.character)) %>%

bind_cols(dummies)

Quick and easy in Python.

Python

dummies = pd.get_dummies(all_dat[nominal_vars], drop_first=True)

all_dat = pd.concat((all_dat.drop(nominal_vars, axis = 1), dummies), sort = False, axis = 1)

As our last step, transform the variables using the Box-Cox method with a fudge factor of +1. I want to get the lambda for each feature so as to normalize that feature accurately. So first, I determine which features have a skewed distribution that I want to transform. I get the lambda for those features and then transform them using that lambda. I drop the skewed columns from the data frame and then bind the transformed features.

R

skewed_vars <-

map_lgl(all_dat %>% select_if(is.numeric), ~ (moments::skewness(.x) > 0.75)) %>% which() %>% names()

lmbdas <- map_dbl(skewed_vars, ~ car::powerTransform(all_dat[[.x]] + 1)$lambda)

trans_vars <- map2_dfc(skewed_vars, lmbdas, ~ car::bcPower(all_dat[[.x]] + 1, lambda = .y))

colnames(trans_vars) <- skewed_vars

all_dat <-

all_dat %>%

select(-all_of(skewed_vars)) %>%

bind_cols(trans_vars)

In Python, the boxcox function from the scipy.stats module automatically calculates lambda if it is not specified.

Python

from scipy.stats import boxcox

numeric_feats = all_dat.dtypes[all_dat.dtypes != "object"].index

skewed_cols = all_dat[numeric_feats].apply(lambda x: skew(x.dropna()))

skewed_cols_idx = skewed_cols[skewed_cols > 0.75].index

skewed_cols = all_dat[skewed_cols_idx]+1

all_dat[skewed_cols_idx] = skewed_cols.transform(lambda x: boxcox(x)[0])

The R and Python approaches produce the same values for lambda. Just double-checking.

R

glue("Lambda value for LowQualFinSF in R is: {car::powerTransform(train[['LowQualFinSF']] + 1)$lambda}")

## Lambda value for LowQualFinSF in R is: -10.00491

Python

xd, lam = boxcox((train['LowQualFinSF'])+1)

print('Lambda value for LowQualFinSF in Python is: %f' % lam)

## Lambda value for LowQualFinSF in Python is: -10.00491

Double-check that there are no missing observations about all this feature engineering.

R

glue("There are {sum(is.na(all_dat))} features with missing observations")

## There are 0 features with missing observations

Python

missing = all_dat.apply(lambda x: x.isnull().sum()) > 0

print('There are {} features with missing observations'.format(missing.sum()))

## There are 0 features with missing observations

Drop sparse features

There are a few sparse features–those that have very, very little variation and so cannot provide much explanatory power. It is safe to drop these. Check the dimensions to make sure that they match in both R and Python.

R

sparse <- all_dat %>%

summarize_if(is.numeric, ~ sum(. == 0)/nrow(all_dat)) %>%

pivot_longer(cols = everything()) %>%

filter(value > 0.9994) %>%

pull(name)

all_dat <- all_dat %>%

select(-one_of(sparse))

glue("The are {ncol(all_dat)} features and {nrow(all_dat)} observations.")

## The are 396 features and 2917 observations.

And now in Python:

Python

# Removing sparse variables

sparse = []

for var in all_dat.columns:

n_zero = (all_dat[var] == 0).sum()

if n_zero / len(all_dat) > 0.9994:

sparse.append(var)

all_dat.drop(columns=sparse, inplace=True)

print("There are {} features and {} observations.".format(all_dat.shape[1], all_dat.shape[0]))

## There are 396 features and 2917 observations.

Finally, scale and center the data

This is so that all the features are on the same scale, which is necessary for some of the algorithms. I find that allowing some of the algorithms which have built-in options to normalize perform better using those built-in methods. However, Xgboost does not have this option, nor do the random forest options. But I find that they perform better with centered and scaled data. So I will create a second, scaled and centered data frame.

In R, I take advantage of {dplyr}’s mutate_all() function, which transforms all the features in one simple line of code. The base function scale() produces a lot of information, much of which we don’t need. We only need the scaled values! So I add [,1] to the code to extract only the values and to make sure that the feature names are preserved. Also, scale()’s has a default setting center = TRUE. I add it here for explicitness, but that it not necessary, since it is the default setting.

R

all_dat_scaled <-

all_dat %>%

mutate_all(~ scale(.)[,1], center = TRUE)

In Python, I use scale() from {Sci-kit learn}.

Python

from sklearn.preprocessing import scale

all_dat_scaled = pd.DataFrame(scale(all_dat), columns=all_dat.columns)

Great, ready to start modeling!

Modeling

The first thing I will do is split the training data into another pair of training and testing. I will fit each model on the training data and evaluate it on the testing data. I need to subset the all_dat data frame to include only the values in the initial training data set and then split into a training and testing set using a 70/30 split. There are many ways to do this here by hand, but there are also a few packages that have functions to accomplish this. I’m particularly fond of initial_split() from the {rsample} package that is part of the {tidymodels} ecosystem. I’m going to use the {tidyverse} ecosystem to tune and model, so I’ll using {rsample} here. The initial_split() function creates a training and testing set that are called using training() and testing(). I will further use cross-validation to for model selection. The vfold_cv() function creates an n-fold cross-validation split in the data set. Here, we use it on the training split of the training data.

R

train_dat <- all_dat %>% slice(1:nrow(train)) %>% janitor::clean_names()

train_dat_scaled <- all_dat_scaled %>% slice(1:nrow(train)) %>% janitor::clean_names()

test_dat <- all_dat %>% slice(nrow(train)+1:nrow(.)) %>% janitor::clean_names()

test_dat_scaled <- all_dat_scaled %>% slice(nrow(train)+1:nrow(.)) %>% janitor::clean_names()

# Add the log of the target back to the training data for modeling

train_dat[["SalePrice"]] <- log(train[["SalePrice"]])

train_dat_scaled[["SalePrice"]] <- log(train[["SalePrice"]])

#sz <- ceiling(nrow(X)*.7)

#

#set.seed(1491)

#train_idx <- sort(sample(nrow(X), sz))

#X_train <- X[train_idx, ]

#X_test <- X[-train_idx, ]

#

#y_train <- y[train_idx]

#y_test <- y[-train_idx]

set.seed(1491)

train_split <- initial_split(train_dat, prob = 0.7)

set.seed(1491)

train_scaled_split <- initial_split(train_dat_scaled, prob = 0.7)

train_cv <- training(train_split) %>% vfold_cv(v = 5)

train_scaled_cv <- training(train_scaled_split) %>% vfold_cv(v = 5)

glue("The training data is {nrow(training(train_split))} rows by {ncol(training(train_split))} columns")

## The training data is 1094 rows by 397 columns

R

glue("The testing data is {nrow(testing(train_split))} rows by {ncol(testing(train_split))} columns")

## The testing data is 364 rows by 397 columns

For Python, after I subset the all_dat data from to include only the data in the initial training dataset, I use the train_test_split() function from sci-kit learn.

Python

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

X = all_dat.iloc[:len(train),:]

X_scaled = all_dat_scaled.iloc[:len(train),:]

y = np.log(train['SalePrice'])

test = all_dat.iloc[len(train):,:]

test_scaled = all_dat_scaled.iloc[len(train):,:]

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(

X, y, test_size=0.3, random_state = 1491)

X_train_scaled, X_test_scaled, y_train_scaled, y_test_scaled = train_test_split(

X_scaled, y, test_size=0.3, random_state = 1491)

print('The training data is {} rows by {} columns'.format(X_train.shape[0], X_train.shape[1]))

## The training data is 1020 rows by 396 columns

Python

print('The testing data is {} rows by {} columns'.format(X_test.shape[0], X_test.shape[1]))

## The testing data is 438 rows by 396 columns

Regularized regression: LASSO

To tune and fit the various models I will try in R, I will use a set of packages from the {tidymodels} ecosystem. These packages were developed, in part, by the creator of the{caret} package and designed to supplant it. To break it down: I will use {parsnip} to define and fit models, {dials} and {tune} to tune the hyperparameters, and {rsample} to cross-validate, and {yardstick} to evaluate the model.

R

lasso_model <-

linear_reg(

penalty = tune(),

mixture = 1) %>%

set_engine("glmnet",

standardize = TRUE)

alphas <- grid_regular(penalty(range = c(-5, 0)), levels = 25)

alphas_py <- alphas %>% pull(penalty)

lasso_cv <-

tune_grid(

formula = SalePrice ~ .,

model = lasso_model,

resamples = train_cv,

grid = alphas,

metrics = metric_set(rmse),

control = control_grid(verbose = FALSE)

)

best_lasso <-

lasso_cv %>%

select_best("rmse", maximize = FALSE)

print(best_lasso)

## # A tibble: 1 x 1

## penalty

## <dbl>

## 1 0.00511

R

best_lasso_model <-

lasso_model %>%

finalize_model(parameters = best_lasso)

lasso_fit <-

best_lasso_model %>%

fit(SalePrice ~ ., training(train_split))

lasso_predictions <- predict(lasso_fit, testing(train_split))

testing(train_split) %>%

select(SalePrice) %>%

bind_cols(lasso_predictions) %>%

rmse(SalePrice, .pred) %>%

pull(.estimate) %>%

{glue("For the LASSO model in R, the RMSE is {round(., 4)}")}

## For the LASSO model in R, the RMSE is 0.1153

Now, in Python, using the same hyperparameters.

Python

from sklearn.metrics import mean_squared_error

from sklearn.linear_model import LassoCV, RidgeCV, ElasticNetCV

from sklearn.model_selection import KFold, GridSearchCV, cross_val_score

K = 5

kf = KFold(n_splits=K, shuffle=True, random_state=1491)

def rmse(y_train, y_pred):

return np.sqrt(mean_squared_error(y_train, y_pred))

alphas = r.alphas_py

lasso = LassoCV(max_iter=1e7,

alphas=alphas,

random_state=1491,

cv=5,

n_jobs=-1,

normalize=True,

positive=True)

lasso.fit(X_train, y_train)

## LassoCV(alphas=[1e-05, 1.6155980984398728e-05, 2.6101572156825386e-05,

## 4.216965034285822e-05, 6.812920690579608e-05,

## 0.00011006941712522103, 0.00017782794100389227,

## 0.0002872984833353666, 0.0004641588833612782,

## 0.0007498942093324559, 0.001211527658628589,

## 0.0019573417814876615, 0.0031622776601683794,

## 0.00510896977450693, 0.00825404185268019, 0.01333521432163324,

## 0...00318846, 0.034807005884284134, 0.05623413251903491,

## 0.09085175756516871, 0.14677992676220705, 0.23713737056616552,

## 0.3831186849557293, 0.618965818891261, 1.0],

## copy_X=True, cv=5, eps=0.001, fit_intercept=True, max_iter=10000000.0,

## n_alphas=100, n_jobs=-1, normalize=True, positive=True,

## precompute='auto', random_state=1491, selection='cyclic', tol=0.0001,

## verbose=False)

Python

lasso_pred = lasso.predict(X_test)

print("For the LASSO model in Python, the RMSE is {}".format(rmse(y_test, lasso_pred).round(4)))

## For the LASSO model in Python, the RMSE is 0.1174

Ridge model

So the second model, I will use ridge regression. While LASSO can attenuate coefficients (or weights, depending on your parlance of choice) to zero, Ridge does not. So if there are variables with little explanatory value, they will be retain in a Ridge model.

R

ridge_model <-

linear_reg(

penalty = tune(),

mixture = 0) %>%

set_engine("glmnet",

standardize = TRUE)

alphas <- grid_regular(penalty(range = c(-5, 0)), levels = 25)

alphas_py <- alphas %>% pull(penalty)

ridge_cv <-

tune_grid(

formula = SalePrice ~ .,

model = ridge_model,

resamples = train_cv,

grid = alphas,

metrics = metric_set(rmse),

control = control_grid(verbose = FALSE)

)

best_ridge <-

ridge_cv %>%

select_best("rmse", maximize = FALSE)

print(best_ridge)

## # A tibble: 1 x 1

## penalty

## <dbl>

## 1 0.237

R

best_ridge_model <-

ridge_model %>%

finalize_model(parameters = best_ridge)

ridge_fit <-

best_ridge_model %>%

fit(SalePrice ~ ., training(train_split))

ridge_predictions <- predict(ridge_fit, testing(train_split))

testing(train_split) %>%

select(SalePrice) %>%

bind_cols(ridge_predictions) %>%

rmse(SalePrice, .pred) %>%

pull(.estimate) %>%

{glue("For the ridge model in R, the RMSE is {round(., 4)}")}

## For the ridge model in R, the RMSE is 0.1239

Again, doing this in Python using the sample values to tune the model.

Python

from sklearn.linear_model import RidgeCV

alphas = r.alphas_py

ridge = RidgeCV(alphas=alphas,

cv=5,

normalize=True)

ridge.fit(X_train, y_train)

## RidgeCV(alphas=array([1.00000000e-05, 1.61559810e-05, 2.61015722e-05, 4.21696503e-05,

## 6.81292069e-05, 1.10069417e-04, 1.77827941e-04, 2.87298483e-04,

## 4.64158883e-04, 7.49894209e-04, 1.21152766e-03, 1.95734178e-03,

## 3.16227766e-03, 5.10896977e-03, 8.25404185e-03, 1.33352143e-02,

## 2.15443469e-02, 3.48070059e-02, 5.62341325e-02, 9.08517576e-02,

## 1.46779927e-01, 2.37137371e-01, 3.83118685e-01, 6.18965819e-01,

## 1.00000000e+00]),

## cv=5, fit_intercept=True, gcv_mode=None, normalize=True, scoring=None,

## store_cv_values=False)

Python

ridge_pred = ridge.predict(X_test)

print("For the Ridge model in Python, the RMSE is {}".format(rmse(y_test, ridge_pred).round(4)))

## For the Ridge model in Python, the RMSE is 0.1243

Elasticnet model

Elasticnet models are in essence a midway between LASSO and Ridge models. In {parsnip}, the mixture() parameter controls the amount of penalty ($L_1$, or LASSO, and $L_2$, or ridge) applied in reguarlized models. In the LASSO model, mixture = 1 and in the ridge model, mixture = 0. For the elasticnet model, we can select a value between 0 and 1. So in this, we tune mixture in addition to penalty.

R

en_model <-

linear_reg(

penalty = tune(),

mixture = tune()) %>%

set_engine("glmnet",

standardize = TRUE)

en_grid <- grid_regular(penalty(range = c(-5, 0)), mixture(c(0.01, 0.95)), levels = 10)

alphas_py <- en_grid %>% pull(penalty) %>% unique() %>% round(5)

l1 <- en_grid %>% pull(mixture) %>% unique()

en_cv <-

tune_grid(

formula = SalePrice ~ .,

model = en_model,

resamples = train_cv,

grid = en_grid,

metrics = metric_set(rmse),

control = control_grid(verbose = FALSE)

)

best_en <-

en_cv %>%

select_best("rmse", maximize = FALSE)

print(best_en)

## # A tibble: 1 x 2

## penalty mixture

## <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 0.0215 0.219

R

best_en_model <-

en_model %>%

finalize_model(parameters = best_en)

en_fit <-

best_en_model %>%

fit(SalePrice ~ ., training(train_split))

en_predictions <- predict(en_fit, testing(train_split))

testing(train_split) %>%

select(SalePrice) %>%

bind_cols(en_predictions) %>%

rmse(SalePrice, .pred) %>%

pull(.estimate) %>%

{glue("For the Elastic Net model in R, the RMSE is {round(., 4)}")}

## For the Elastic Net model in R, the RMSE is 0.1151

One thing to notice about Python and {Sci-kit learn} compared to R and {glmnet} (which {parsnip} uses to implment regularized linear models) is that the LASSO, ridge, and elasticnet are implemented in different functions. In {glmnet}, these are implemented in the same function. So if we set l1=1 or l1=0 in ElasticNetCV(), we’d get the LASSO and ridge, respectively.

Python

alphas = r.alphas_py

l1 = r.l1

elasticnet = ElasticNetCV(max_iter=1e7,

alphas=alphas,

l1_ratio=l1,

cv=5)

elasticnet.fit(X_train, y_train)

## ElasticNetCV(alphas=[1e-05, 4e-05, 0.00013, 0.00046, 0.00167, 0.00599, 0.02154,

## 0.07743, 0.27826, 1.0],

## copy_X=True, cv=5, eps=0.001, fit_intercept=True,

## l1_ratio=[0.01, 0.11444444444444443, 0.21888888888888888,

## 0.3233333333333333, 0.42777777777777776,

## 0.5322222222222222, 0.6366666666666666,

## 0.741111111111111, 0.8455555555555555, 0.95],

## max_iter=10000000.0, n_alphas=100, n_jobs=None, normalize=False,

## positive=False, precompute='auto', random_state=None,

## selection='cyclic', tol=0.0001, verbose=0)

Python

elasticnet_pred = elasticnet.predict(X_test)

print("For the Elastic Net model in Python, the RMSE is {}".format(rmse(y_test, elasticnet_pred).round(4)))

## For the Elastic Net model in Python, the RMSE is 0.1162

MARS model

R

mars_model <-

mars(

mode = "regression",

prod_degree = tune(),

prune_method = tune()

) %>%

set_engine("earth")

mars_grid <-

grid_regular(

prod_degree(),

prune_method(c('backward', 'none', 'exhaustive', 'forward', 'seqrep')),

levels = 5

)

mars_tune <-

tune_grid(

formula = SalePrice ~ .,

model = mars_model,

resamples = train_cv,

grid = mars_grid,

metrics = metric_set(rmse),

control = control_grid(verbose = FALSE)

)

best_mars <-

mars_tune %>%

select_best("rmse", maximize = FALSE)

print(best_mars)

## # A tibble: 1 x 2

## prod_degree prune_method

## <int> <chr>

## 1 1 exhaustive

R

mars_fit <-

mars_model %>%

finalize_model(parameters = best_mars) %>%

fit(SalePrice ~ ., training(train_split))

## Exhaustive pruning: number of subsets 2.7e+11 bx sing val ratio 6.9e-06

R

mars_predictions <-

testing(train_split) %>%

select(SalePrice) %>%

bind_cols(

predict(mars_fit, testing(train_split))

)

testing(train_split) %>%

select(SalePrice) %>%

bind_cols(mars_predictions) %>%

rmse(SalePrice, .pred) %>%

pull(.estimate) %>%

{glue("For the MARS model in R, the RMSE is {round(., 4)}")}

## For the MARS model in R, the RMSE is 0.1148

Python

from pyearth import Earth

mars_model = Earth(max_degree = 1, enable_pruning=True)

mars_model.fit(X_train, y_train)

## Earth(allow_linear=None, allow_missing=False, check_every=None,

## enable_pruning=True, endspan=None, endspan_alpha=None, fast_K=None,

## fast_h=None, feature_importance_type=None, max_degree=1, max_terms=None,

## min_search_points=None, minspan=None, minspan_alpha=None, penalty=None,

## smooth=None, thresh=None, use_fast=None, verbose=0, zero_tol=None)

Python

mars_pred = mars_model.predict(X_test)

print("For the MARS model in Python, the RMSE is {}".format(rmse(y_test, mars_pred).round(4)))

## For the MARS model in Python, the RMSE is 0.1262

XGBoost

In contrast to the previous set of model, eXtreme gradient boosting (XGBoost) is a tree-based model. I kind of figure that regular old-fashioned linear models will perform well on these data, given the pretty much linear relationship between housing prices and house features. But tree-based models have advantages and can get a lot of traction out of weak predictors.

These models take a long time to run, so I have run them, determined the best parameters and plugged those in, so that this script will run in a reasonable amount of time.

R

# R Parsnip to Python translator:

# sample_size = subsample

# loss_reduction = gamma

# trees = n_estimators

# tree_depth = max_depth

# min_n = min_child_weight

# mtry = colsample_bytree

#xgb_model <-

# boost_tree(

# mode = "regression",

# trees = tune(),

# learn_rate = tune(),

# min_n = tune(),

# tree_depth = tune()

# ) %>%

# set_engine(

# "xgboost",

# booster = "gbtree"

# )

#

#xgb_grid <-

# grid_regular(

# trees(c(100, 1000)),

# learn_rate(c(-4, 0)),

# min_n(c(2, 10)),

# tree_depth(c(2, 8)),

# levels = 3

# )

#

#learn_rate_py <- xgb_grid %>% pull(learn_rate) %>% unique()

#min_n_py <- xgb_grid %>% pull(min_n) %>% unique()

#tree_depth_py <- xgb_grid %>% pull(tree_depth) %>% unique()

#

#xgb_tune <-

# tune_grid(

# formula = SalePrice ~ .,

# model = xgb_model,

# resamples = train_cv,

# grid = xgb_grid,

# metrics = metric_set(rmse),

# control = control_grid(verbose = TRUE)

# )

#

#best_xgb <-

# xgb_tune %>%

# select_best("rmse", maximize = FALSE)

#

#print(best_xgb)

#

#xgb_fit <-

# xgb_model %>%

# finalize_model(parameters = best_xgb) %>%

# fit(SalePrice ~ ., training(train_split))

xgb_model <-

boost_tree(

mode = "regression",

trees = 2000,

sample_size = 0.5,

mtry = 1,

loss_reduction = 0.001,

learn_rate = 0.01,

min_n = 10,

tree_depth = 5

) %>%

set_engine(

"xgboost",

booster = "gbtree"

)

xgb_fit <-

xgb_model %>%

fit(SalePrice ~ ., training(train_scaled_split))

xgb_predictions <-

testing(train_split) %>%

select(SalePrice) %>%

bind_cols(

predict(xgb_fit, testing(train_scaled_split))

)

testing(train_scaled_split) %>%

select(SalePrice) %>%

bind_cols(xgb_predictions) %>%

rmse(SalePrice, .pred) %>%

pull(.estimate) %>%

{glue("For the XGBoost model in R, the RMSE is {round(., 4)}")}

## For the XGBoost model in R, the RMSE is 0.1136

Again, to save time for the Python implementation of XGBoost, I use the parameters determined by the grid search in R. Not fair to Python, but it does save time.

Python

from xgboost import XGBRegressor

xgb = XGBRegressor(booster='gbtree',

objective='reg:squarederror',

eta = 0.01,

subsample=0.5,

gamma = 0.001,

n_estimators=2000,

colsample_bytree=1,

max_depth=5,

min_child_weight=10,

random_state=1491)

xgb_model = xgb.fit(X_train, y_train)

xgb_pred = xgb_model.predict(X_test)

print("For the XGBoost model in Python, the RMSE is {}".format(rmse(y_test, xgb_pred).round(4)))

## For the XGBoost model in Python, the RMSE is 0.1282